Small Country Read online

This is a work of fiction. Names, characters, places, and incidents either are the product of the author’s imagination or are used fictitiously. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, events, or locales is entirely coincidental.

Translation copyright © 2018 by Sarah Ardizzone

All rights reserved.

Published in the United States by Hogarth, an imprint of the Crown Publishing Group, a division of Penguin Random House LLC, New York.

crownpublishing.com

HOGARTH is a trademark of the Random House Group Limited, and the H colophon is a trademark of Penguin Random House LLC.

Originally published in France as Petit Pays by Éditions Grasset in 2016. Copyright © Éditions Grasset & Fasquelle, 2016. Éditions Grasset is grateful to Catherine Nabakov for contributing to the publication of this work.

This book is supported by the Institut français du Royaume-Uni as part of the Burgess Programme.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available upon request.

ISBN 9781524759872

Ebook ISBN 9781524759896

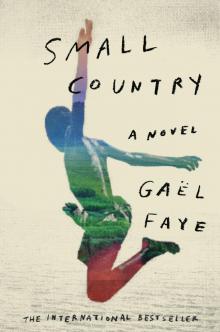

Cover design by Rachel Willey

Cover photographs by (figure) Mwangi Kirubi; (landscape inside figure) Patrick Rudolph

v5.3.1

ep

Contents

Cover

Title Page

Copyright

Dedication

Prologue

Chapter 1

Chapter 2

Chapter 3

Chapter 4

Chapter 5

Chapter 6

Chapter 7

Chapter 8

Chapter 9

Chapter 10

Chapter 11

Chapter 12

Chapter 13

Chapter 14

Chapter 15

Chapter 16

Chapter 17

Chapter 18

Chapter 19

Chapter 20

Chapter 21

Chapter 22

Chapter 23

Chapter 24

Chapter 25

Chapter 26

Chapter 27

Chapter 28

Chapter 29

Chapter 30

Chapter 31

About the Author

For Jacqueline

Prologue

I really don’t know how this story began.

Papa tried explaining it to us one day in the pick-up truck.

“In Burundi, you see, it’s like in Rwanda. There are three different ethnic groups. The Hutu form the biggest group, and they’re short with wide noses.”

“Like Donatien?” I asked.

“No, he’s from Zaire, that’s different. Like our cook, Prothé, for instance. There are also the Twa pygmies. But we won’t worry about them, there are so few they hardly count. And then there are the Tutsi, like your mother. The Tutsi make up a much smaller group than the Hutu, they’re tall and skinny with long noses and you can never tell what’s going on inside their heads. Take you, Gabriel,” he said, pointing at me, “you’re a proper Tutsi: we can never tell what you’re thinking.”

I had no idea what I was thinking, either. What was anyone supposed to make of all that? So I asked a question instead:

“The war between Tutsis and Hutus…is it because they don’t have the same land?”

“No, they have the same country.”

“So…they don’t have the same language?”

“No, they speak the same language.”

“So, they don’t have the same God?”

“No, they have the same God.”

“So…why are they at war?”

“Because they don’t have the same nose.”

And that was the end of the discussion. It was all very odd. I’m not sure Papa really understood it, either. From that day on, I started noticing people’s noses in the street, as well as how tall they were. When my little sister Ana and I went shopping in town, we tried to be subtle about guessing who was Hutu and who was Tutsi.

“The guy in white trousers is a Hutu,” we would whisper, “he’s short with a wide nose.”

“Right, and the one towering over everybody in a hat, he’s extra-skinny with a long nose, so he must be a Tutsi.”

“See that man over there, in the striped shirt? He’s a Hutu.”

“No, he’s not—look, he’s tall and skinny.”

“Yes, but he’s got a wide nose!”

That’s when we began to have our suspicions about this whole ethnic story. Anyway, Papa didn’t want us talking about it. He thought children should stay out of politics. But we couldn’t help it. The atmosphere was becoming stranger by the day. At school, fights broke out at the slightest provocation, with friends calling each other “Hutu” or “Tutsi” as an insult. When we were all watching Cyrano de Bergerac, one student was even overheard saying: “Look, with a nose like that he’s got to be Tutsi.” Something in the air had changed. And you could smell it, no matter what kind of nose you had.

I am haunted by the idea of returning. Not a day goes by without the country calling to me. A secret sound, a scent on the breeze, a certain afternoon light, a gesture, sometimes silence is enough to stir my childhood memories. “You won’t find anything there, apart from ghosts and a pile of ruins,” Ana keeps telling me. She refuses to hear another word about that “cursed country.” I listen and I believe her. She’s always been more clear-headed than me. So I put it out of my mind. I decide, once and for all, that I’m never going back. My life is here. In France.

Except that I no longer live anywhere. Living somewhere involves a physical merging with its landscape, with every crevice of its environment. There’s none of that here. I’m passing through. I rent. I crash. I squat. My town is a dormitory that serves its purpose. My apartment smells of fresh paint and new linoleum. My neighbors are perfect strangers, we avoid each other politely in the stairwell.

I live and work just outside Paris. In Saint-Quentin-en-Yvelines. RER line C. This new town is like a life without a past. It took me years to feel “integrated.” To hold down a stable job, an apartment, hobbies, friendships.

I enjoy connecting with people online. Encounters that last an evening or a few weeks. The girls who date me are all different, each one beautiful in her own way. I feel intoxicated listening to them, inhaling the fragrance of their hair, before surrendering to the warm oblivion of their arms, their legs, their bodies. Not one of them fails to ask me the same nagging question, and it’s always on our first date: “So, where are you from?” A question as mundane as it is predictable. It feels like an obligatory rite of passage, before the relationship can develop any further. My skin—the color of caramel—must explain itself by offering up its pedigree. “I’m a human being.” My answer rankles with them. It’s not that I’m trying to be provocative. Any more than I want to appear pedantic or philosophical. But when I was just knee-high to a locust, I had already made up my mind never to define myself again.

The evening progresses. My technique is smooth. They talk. They enjoy being listened to. I am drunk. Deep in my cups. Drowning in alcohol, I shrug off sincerity. I become a fearsome hunter. I make them laugh. I seduce them. Just for fun, I return to the question of my roots, deliberately keeping the mystery alive. We play at cat-and-mouse. I inform them, with cold cynicism, that my identity can be weighed in corpses.

They don’t react. They try to keep things light. They stare at me with doe-like eyes. I want them. Sometimes, they give themselves up. They take me for a bit of a character. But I can entertain them for only so long.

I am haunted by the idea of returning but I keep putting it off, indefinitely. There’s the fear of buried truths, of nightmares left on the threshold of my native land. For twenty years I’ve been going back there—in my dreams at night, in the magical thinking of my days—back to my neighborhood, to our street where I lived happily with my family and friends. My childhood has left its marks, and I don’t know what to do about this. On good days, I tell myself it has made me strong and sensitive. But when I’m staring at the bottom of a bottle, I blame my childhood for my failure to adapt to the world.

My life is one long meandering. Everything interests me. Nothing ignites my passion. There’s no fire in my belly. I belong to the race of slouchers, of averagely inert citizens. Every now and again I have to pinch myself. I notice the way I behave in company, at work, with my office colleagues. Is that guy in the lift mirror really me? The young man forcing a laugh by the coffee machine? I don’t recognize him. I have come from so far that I still feel astonished to be here. My colleagues talk about the weather or what’s on TV. I can’t listen to them anymore. I’m having trouble breathing. I loosen my shirt collar. My clothes restrict me. I stare at my polished shoes: they gleam, offering a disappointing reflection. What has become of my feet? They’re in hiding. I never walk barefoot outdoors these days. I wander over to the window. Under the low-hanging sky, through the gray sticky drizzle, there’s not a single mango tree in the tiny park wedged between the shopping center and the railway lines.

* * *

—

This particular evening, on leaving work, I run for refuge to the nearest bar, opposite the station. I sit down by the table football and order a whiskey to celebrate my thirty-third birthday. I try ringing Ana, but she’s not answering her mobile. I refuse to give up, redialing her number several times, until I remember she’s on a business trip in London. I want to talk to her, to tell her about the phone call I received this morning. It must be a sign. I have to return, if only to be clear in my own mind. To bring this obsessive story to an end, once and for all. To close the door behind me. I order another whiskey. The noise from the television above the bar temporarily drowns out my thoughts. A twenty-four-hour news channel is broadcasting images of people fleeing war. I witness their makeshift boats washing up on European soil. The children who disembark are frozen, starving, dehydrated. Their lives played out on the global football pitch of insanity. Whiskey in hand, I watch them from the comfort of my VIP box. Public opinion holds that they’ve fled hell to find El Dorado. Bullshit! What about the country inside them?—nobody ever mentions that. Poetry may not be news. But it is all that human beings retain from their journey on this earth. I avert my gaze from images that capture reality, if not the truth. Perhaps those children will write the truth, one day. I’m as gloomy as a motorway service station in winter. Every birthday it’s the same: this intense melancholy that comes crashing down on me like a tropical downpour when I think about Papa, Maman, my friends, and that never-ending party with the crocodile at the bottom of our garden…

1

I’ll never know the true cause of my parents’ separation. There must have been some fundamental misunderstanding from the outset—a manufacturing flaw in their encounter, an asterisk nobody saw or wanted to see. Back then, my parents were young and good-looking. Their hearts puffed up with hope, like the sun that shone on African independence. What a sight! On their wedding day, Papa was astonished to have slipped a ring onto his beloved’s finger. My father didn’t lack charm, of course, with his piercing green eyes, his chestnut hair streaked with blond and his Viking stature. But Maman was head and shoulders above him—even her ankles were legendary! They hinted at long, lithe limbs that turned women’s stares into daggers and made men dream of half-open shutters. Papa was a young Frenchman from the Jura who had arrived in Africa by accident, for his voluntary service, and who came from a village set in mountains that bore a striking resemblance to the Burundian countryside. Except that, back where he came from, none of the women could compete with Maman’s elegance, there were no slender freshwater reeds, no beauties slim as skyscrapers with ebony skin and eyes as wide as those of the Ankole cattle. What music! On their wedding day, a careless rumba escaped some out-of-tune guitars as happiness crooned cha-cha-cha numbers beneath a sky pricked with stars. They could see it all. What mattered was this: Loving. Living. Laughing. Being. Forging ahead, never faltering, to the ends of the earth, and even beyond.

The trouble was that my parents were two lost teenagers suddenly asked to grow into responsible adults. Scarcely had they left behind the hormones and sleepless nights of puberty than it was time to clear away the drained bottles, empty the ashtrays of joint butts, put the psychedelic rock records back into their sleeves, and fold up their bell-bottomed trousers and Indian shirts. A bell had tolled, signaling the arrival—too sudden, too soon—of children, taxes, worries, and responsibilities. Alongside these came growing uncertainty, rampant banditry, dictators and military coups, Structural Adjustment Programmes, forgotten ideals, and mornings that struggled to break, the sun lingering in bed a little longer each day. Reality had struck. And it was a cruel blow. Their carefree beginnings transformed into a rhythm as tyrannical as the relentless ticking of a clock. What had come so naturally at first was now backfiring on my parents, as it dawned on them that they had confused desire with love, and that each of them had invented qualities in the other. It turned out they hadn’t shared dreams, merely illusions. True, each of them had nurtured a dream, but it amounted to nothing more than their own selfish hopes, with neither of them ready to fulfill the other’s expectations.

Still, back then, before all that, before this story I’m about to tell, ours was a happy, uncomplicated existence. Life was the way it was, the way it had always been, the way I wanted it to stay. A gentle, peaceful slumber, no mosquito dancing in my ear, no deluge of questions drumming on the corrugated iron of my head. In those happy times, if anyone asked me, “Life’s good?” I would always answer: “Life’s good!” Wham-bam. When you’re happy, you don’t think twice about it. It was only afterward that I began to consider the question. Weighing up the pros and cons. Being evasive, as I nodded vaguely. And it wasn’t just me—the whole country was at it. People only ever replied with: “Not bad.” Because life could no longer be altogether good, after everything that had happened to us.

2

The beginning of the end of our happy days goes back, I think, to that Feast of Saint-Nicholas, out on Jacques’s large terrace in Bukavu, Zaire. Once a month we paid old Jacques a visit, it had become our tradition. Maman joined us that day, although she had barely said a word to Papa in several weeks. Before setting off, we went to the bank to pick up some local currency. “We’re millionaires!” said Papa as we left the building. In Mobutu’s Zaire, hyperinflation meant paying for a glass of water with banknotes of five million zaires.

The border checkpoint marked our entry into another world. Burundian restraint gave way to Zairean commotion. In the unruly crowd, people greeted one another, heckled or hurled abuse as if at a cattle market. Dirty, noisy kids eyed up wing mirrors, windscreen wipers, and hubcaps splattered from stagnant puddles, calculating their street value; grilled goat-meat skewers—brochettes—were up for grabs in exchange for a few wheelbarrows of cash; young mothers, zigzagging between the tailbacks of goods vehicles and minibuses jammed bumper to bumper, hawked bags of spicy peanuts, and hard-boiled eggs for dipping in coarse salt; beggars, with legs corkscrewed by polio, pleaded for a few million zaires to help them survive the unfortunate consequences of the fall of the Berlin Wall; and a preacher standing on the hood of his battered Mercedes, wielding a Swahili Bible bound in royal python skin, announced the end of the world at the top of his voice.

Inside his rusty sentry box, a dozing soldier waved a fly-swatter in desultory fashion, the stench of diesel combining with hot air to parch the throat of one more long-term unpaid functionary. On the roads, vast craters spawned from old potholes gave the cars a bumpy ride. Not that this prevented the customs officer from meticulously inspecting each vehicle, checking tire tread depth or engine water levels, as well as ensuring that the indicators were in good working order. In the event of the car or truck failing to produce any of these desired shortcomings, the customs officer would insist on a certificate of baptism or first communion to qualify for entry into the country.

Papa was battle-weary that afternoon and in the end paid the bribe all those ludicrous checks had really been about. The barrier rose at last and we drove on through the steam from the hot-water springs dotted along the side of the road.

After the small town of Uvira and before Bukavu we stopped off at some roadside gargotes to buy banana doughnuts and paper cones of fried ants. There were all kinds of fantastical signs advertizing these cheap eateries: Au Fouquet’s des Champs-Elysées…Snack-bar Giscard d’Estaing…Restaurant fête comme chez vous…When Papa took out his Polaroid camera to capture the local spirit of inventiveness, Maman sucked her teeth and berated him for marveling at an exoticism concocted for whites.

After nearly running over a multitude of roosters, ducks, and children, we arrived in Bukavu—a sort of Garden of Eden on the banks of Lake Kivu and an art deco relic of a town that had once been Futurist. At Jacques’s house the table had already been laid to welcome us. He had ordered in fresh prawns from Mombasa.

Small Country

Small Country